Tue Dec 04, 2018 1:17 pm

#1655361

60 years ago today!

Holy Kremoly

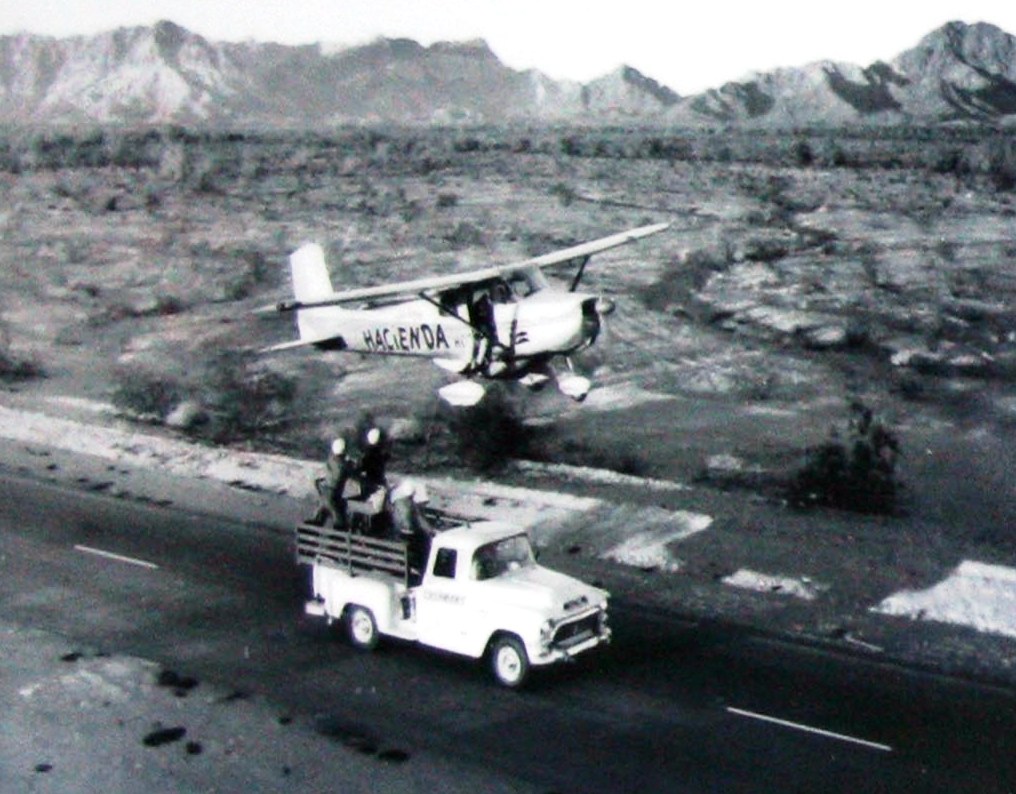

Robert Timm and John Cook took off from McCarran Airfield in Las Vegas, Nevada, in a used Cessna 172, registration number N9172B. Sixty-four days, 22 hours, 19 minutes and 5 seconds later, they landed back at McCarran Airfield on February 4, 1959.

The flight was part of a fund-raising effort for the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund. Food and water were transferred by matching speeds with a chase car on a straight stretch of road in the desert, and hoisting the supplies aboard with a rope and bucket. Fuel was taken on by hoisting a hose from a fuel truck up to the aircraft, filling an auxiliary belly tank installed for the flight, pumping that fuel into the aircraft's regular tanks and then filling the belly tank again. The drivers steered while a second person matched speeds with the aircraft with his foot on the vehicle's accelerator pedal. Engine oil was added by means of a tube from the cabin that was fitted to pass through the firewall.

Only the pilot's seat was installed. The remaining space was used for a pad on which the relief pilot slept. The right cabin door was replaced with an easy-opening, accordion-type door to allow supplies and fuel to be hoisted aboard.

Early in the flight, the engine-driven electric generator failed. A Champion wind-driven generator (turned by a small propeller) was hoisted aboard, taped to the wing support strut, and plugged into the cigarette lighter socket; it served as the aircraft's source of electricity for the rest of the flight.

The pilots decided to end the marathon flight because with 1,558 hours of continuously running the engine during the record-setting flight, plus several hundred hours already on the engine beforehand (considerably in excess of its normal overhaul interval), the engine's power output had deteriorated to the point where they were barely able to climb away after refueling.

The aircraft is on display in the passenger terminal at McCarran International Airport. Photos and details of the record flight can be seen in a small museum on the upper level of the baggage claim area.[13]

After the flight, Cook said: “Next time I feel in the mood to fly endurance, I'm going to lock myself in our garbage can with the vacuum cleaner running. That is, until my psychiatrist opens up for business in the morning.”

Holy Kremoly

FLYER Club Member

FLYER Club Member